Is White-Label Stablecoin Issuance Commoditized?

Token plumbing is converging. Outcomes aren’t.

Welcome to Stablecoin Blueprint, the weekly analysis about the opportunities and growth strategies in Stablecoin Payments and Onchain Finance

Got feedback or suggestions? Reply to this email or find my contact details online.

Introduction: Everyone is issuing stablecoins

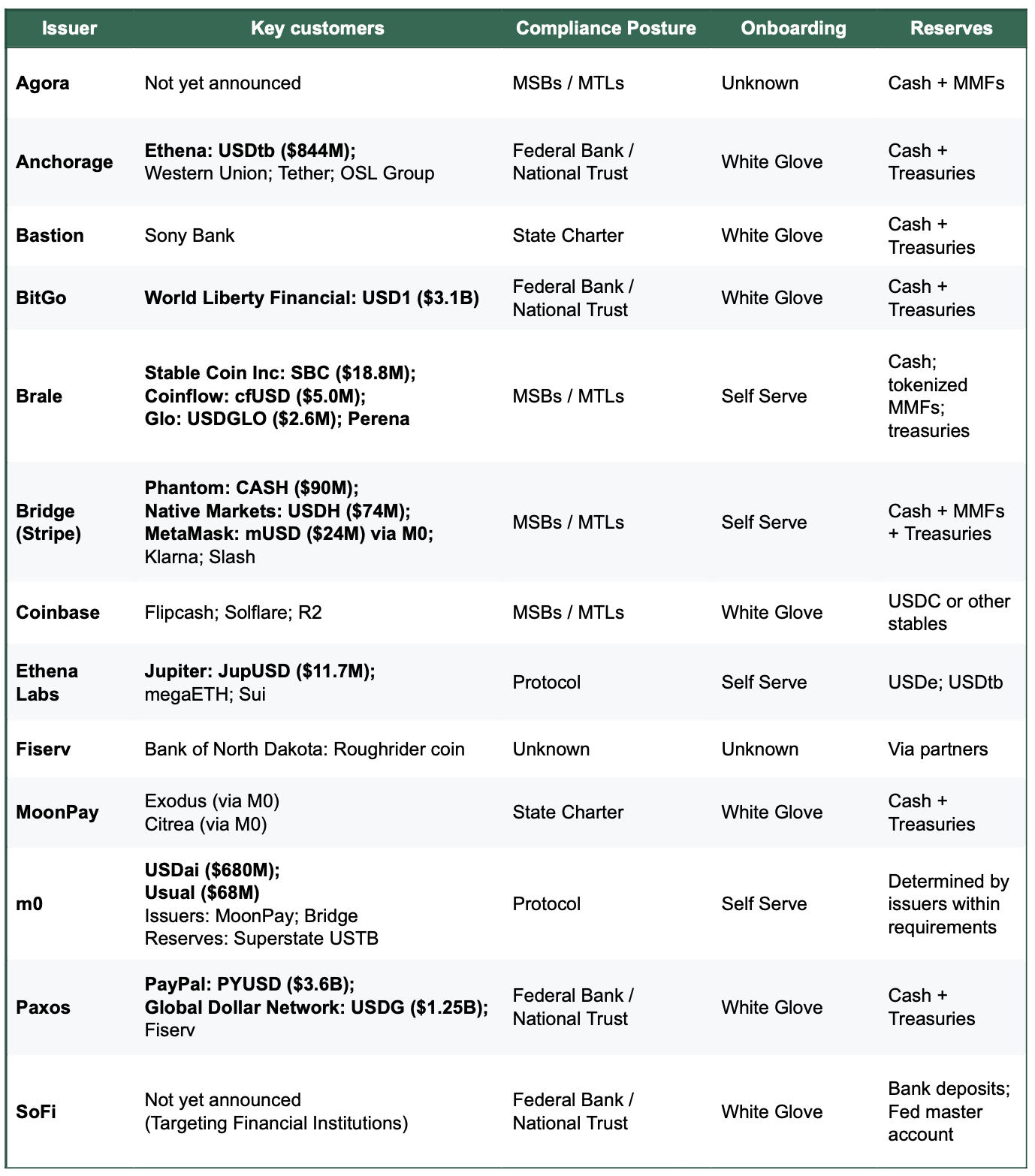

Stablecoins are turning into application-level financial infrastructure. With clearer rules after the GENIUS Act, brands like Western Union, Klarna, Sony Bank, and Fiserv are moving from “integrate USDC” to “ship our own dollar” using white-label issuance partners.

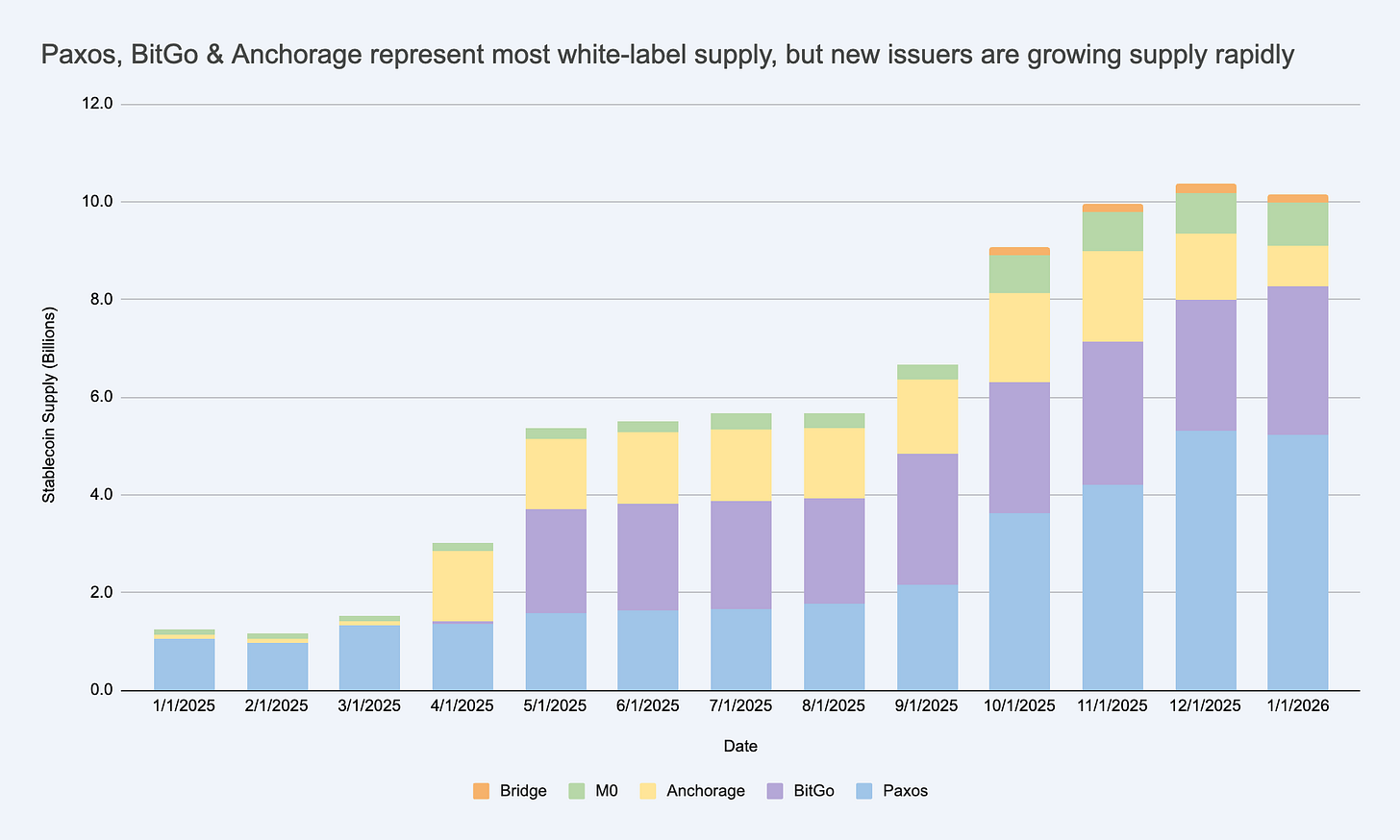

What’s enabling that shift is the proliferation of stablecoin issuance-as-a-service platforms. A few years ago, the shortlist was basically Paxos. Today there are 10+ credible paths depending on what you’re building, including newer platforms like Bridge and MoonPay, regulatory-first players like Anchorage, and large incumbents like Coinbase.

That abundance makes issuance look commoditized. And at the token-plumbing layer, it increasingly is. But “commoditized” depends on the buyer and the job-to-be-done. Once you separate token plumbing from liquidity operations, regulatory posture, and the surrounding bundle (ramps, orchestration, accounts, cards), the market looks less like a race to zero and more like segmented competition, with pricing power concentrating where outcomes are hardest to replicate.

In other words: core issuance is converging, but substitution isn’t trivial where outcomes are operationally demanding (compliance, redemption, time to launch, bundled services).

If you treat issuers as interchangeable, you’ll miss where the real constraints live, and where margins are likely to survive.

Why are companies launching branded stablecoins anyway?

Fair question. Companies do it for three main reasons:

Economics: keep more value from customer activity (balances and flows), and access adjacent revenue (treasury, payouts, lending, cards).

Control behavior: embed custom rules and incentives (e.g. loyalty), and choose settlement paths and interoperability that match your product.

Move faster: stablecoins let teams ship new financial experiences globally without rebuilding the full banking stack.

Importantly, most branded coins don’t need to become USDC-scale to be “successful”. In a walled or semi-open garden, the KPI is not necessarily market cap. It can be ARPU and unit economics increases: how much more revenue, retention, or efficiency the stablecoin feature unlocks.

How does white-label issuance work? Breaking down the stack

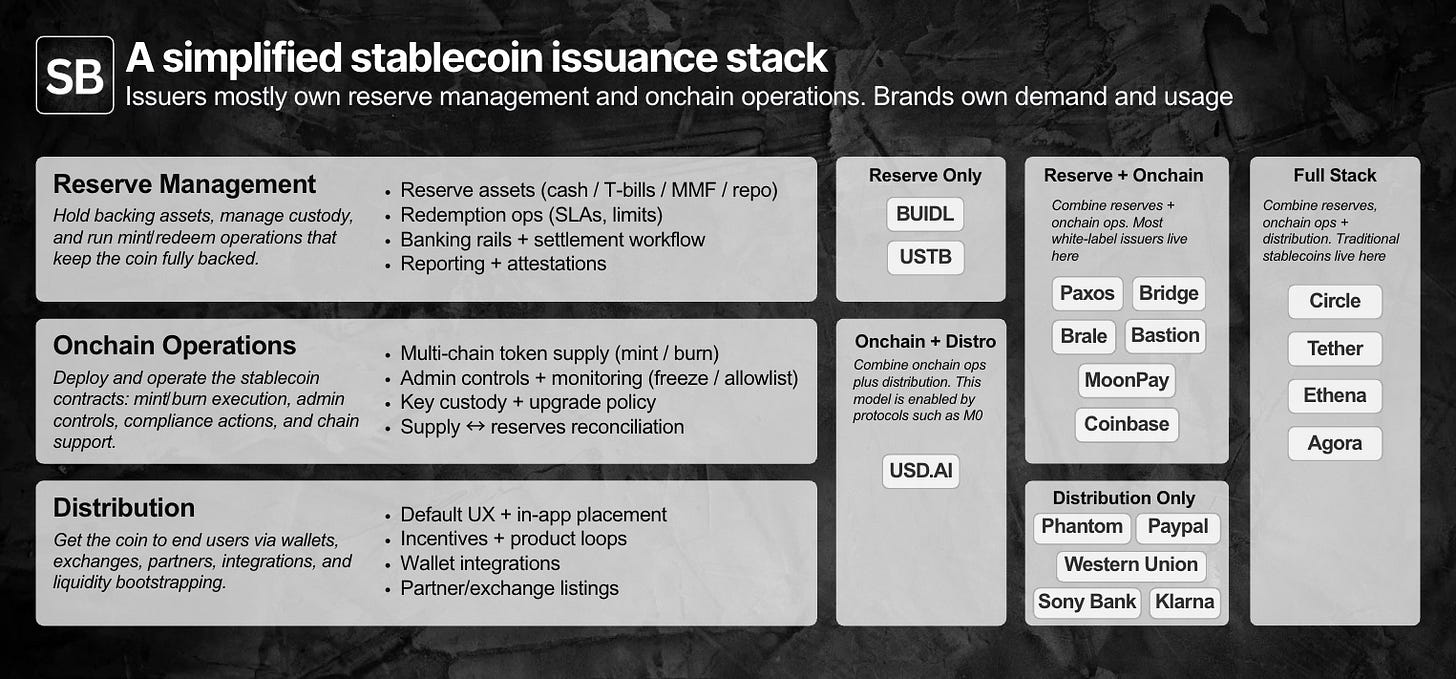

To judge whether issuance is “commoditized,” we first need to define the jobs being done: reserve management, smart contract + onchain operations, and distribution.

White-label issuance lets a company (the brand) launch and distribute a branded stablecoin while outsourcing the first two layers to an issuer-of-record.

In practice, ownership falls into two buckets:

Mostly brand-owned: distribution. Where the coin is used, the default UX, wallet placement, and which partners or venues support it.

Mostly issuer-owned: issuance operations. The smart contract layer (token rules, admin controls, mint/burn execution) and the reserve layer (reserve assets, custody, redemption operations).

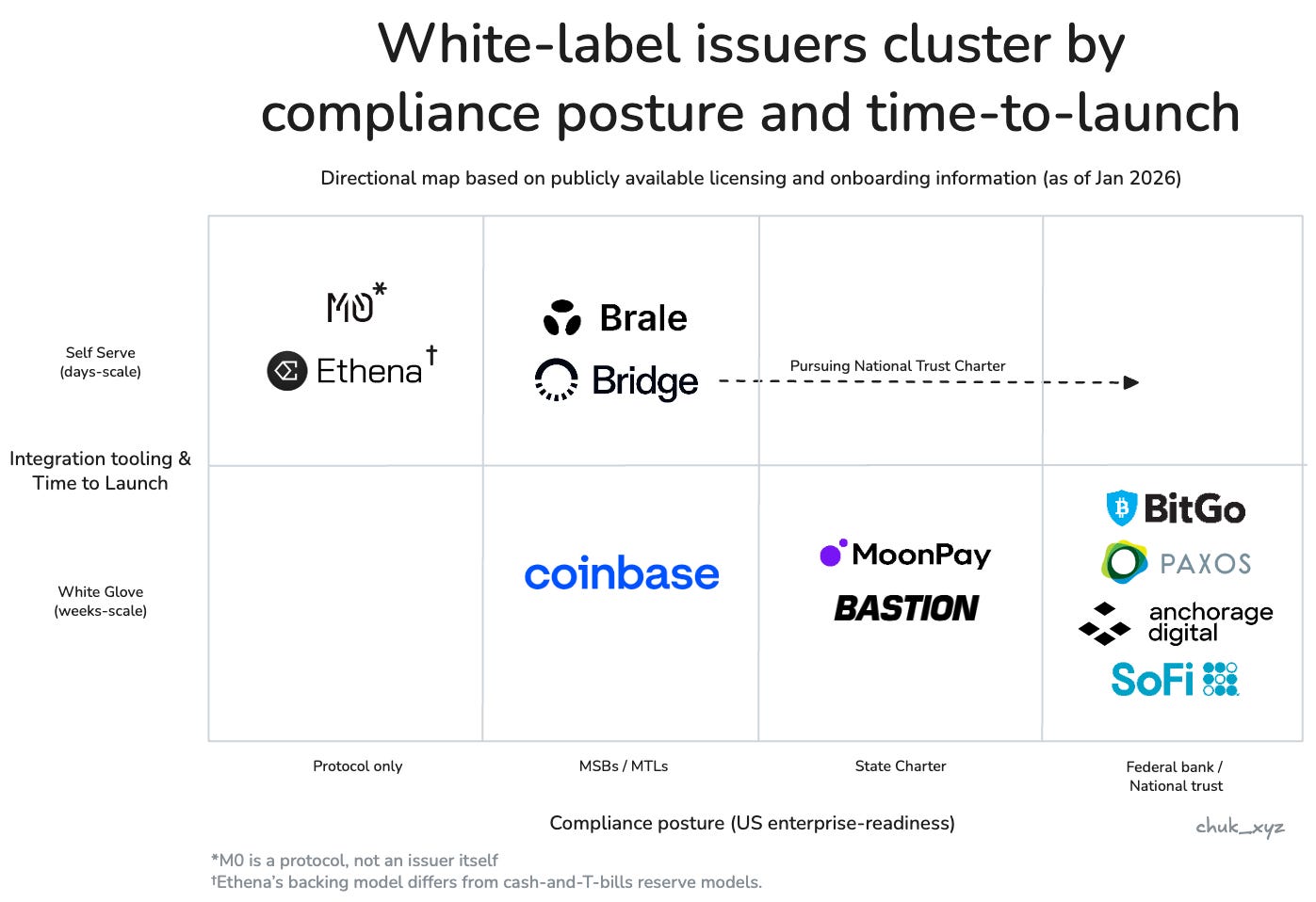

Operationally, much of this is now productized via APIs and dashboards, with launch timelines ranging from days to weeks depending on complexity. Not every program needs a U.S.-compliant issuer today, but for issuers targeting U.S. enterprise buyers, compliance posture is already part of the product even ahead of formal GENIUS enforcement.

Distribution is the hardest part. Inside a walled garden, getting the coin used is mostly a product decision. Outside it, integrations and liquidity become the bottleneck, and issuers often blur the boundary by helping with secondary liquidity (exchange/MM relationships, incentives, seeding). Brands still own demand, but this “go-to-market support” is one of the places issuers can change outcomes materially.

Different buyers weight these responsibilities differently, which is why the issuer market splits into distinct clusters.

The market splits into clusters. Commoditization is buyer-dependent

Commoditization is when a service becomes standardized enough that providers are interchangeable without changing outcomes, pushing competition toward price and away from differentiation.

If swapping issuers changes the outcome you care about, issuance isn’t commoditized for you.

At the token-plumbing layer, swapping issuers often doesn’t change outcomes, so it’s increasingly interchangeable. Many issuers can hold treasury-like reserves, deploy audited mint/burn contracts, ship baseline admin controls (pause/freeze), support the major chains, and expose similar APIs.

But brands are rarely buying simple token deployment. They are buying outcomes, and the required outcomes are heavily dependent on the buyer type. The market directionally splits into a few clusters, each with a different point where substitution breaks. Within each cluster, teams tend to end up with a handful of viable options in practice.

Enterprise and financial institutions are procurement-led and optimize for trust. Substitution breaks on compliance credibility, custody standards, governance, and 24/7 redemption reliability at scale (think hundreds of millions). In practice this is a “risk committee” purchase: the issuer has to be defensible on paper and operationally boring in production.

Examples: Paxos, Anchorage, BitGo, SoFi

Fintechs and consumer wallets are product-led and optimize for shipping and distribution. Substitution breaks on time-to-launch, integration depth, and the supporting value-added rails (e.g. on/off ramps) that make the coin usable in real workflows. In practice this is a “ship it this sprint” purchase: the winning issuer is the one that minimizes KYC/ramps/orchestration work and gets your whole feature live fastest, not just the stablecoin.

Examples: Bridge, Brale (Moonpay/Coinbase likely live here too but public details are scarce).

DeFi and investment platforms are onchain-native and optimize for composability and programmability, including designs that optimize yield at the cost of different risk tradeoffs. Substitution breaks on reserve model design, liquidity dynamics, and onchain integrations. In practice this is a “design constraints” purchase: teams will accept different reserve mechanics if it improves composability or yield.

Examples: Ethena Labs, M0 protocol

Differentiation is moving up the stack, this is visible clearly in the fintech/wallet segment. As issuance becomes a feature, issuers compete by bundling adjacent rails that complete the job and assist with distribution: compliant on/off-ramps and virtual accounts, payments orchestration, custody, and card issuance. This can preserve pricing power by changing time-to-market and operational outcomes.

With that framing, the commoditization question becomes clear.

Stablecoin issuance is commoditized at the token layer, but not yet at the outcome layer, because buyer constraints make providers non-substitutable.

As the market develops, issuers that serve each cluster will may converge on similar offerings required to serve that market, but we haven’t reached that point yet.

Where might durable advantage come from?

If token plumbing is already table stakes, and differentiation on the edges is slowly eroding, the obvious question is whether any issuer can build a durable moat. Right now, it mostly looks like a customer acquisition play with retention via switching costs. Changing issuers touches reserves/custody ops, compliance workflows, redemption behavior, and downstream integrations, so issuers are not “one-click replaceable.”

Beyond bundling, the most plausible long-term moat is network effects. If branded coins increasingly need seamless 1:1 convertibility and shared liquidity, value may accrue to the issuer or protocol layer that becomes the default interoperability network. The open question is whether that network is issuer-owned (strong capture) or a neutral standard (broad adoption, weaker capture).

The pattern worth watching: does interoperability become a commodity feature, or the main source of pricing power?

Conclusion

In summary:

Issuance is commoditized at the core, differentiated at the edges, for now. Token deployment and baseline controls are converging. Outcomes still diverge where operations, liquidity support, and integrations matter.

For any given buyer, the market is less crowded than it looks. Real constraints narrow the shortlist quickly, and “credible options” are often a handful, not ten.

Pricing power comes from bundling, regulatory posture and liquidity constraints. The value is less “token creation” and more the surrounding rails that make a stablecoin usable in production.

It’s still unclear which moats are sustainable. Network effects via shared liquidity and convertibility standards are a plausible path, but it’s not obvious who captures value as interoperability matures.

What to watch next: whether branded stablecoins converge on a small number of convertibility networks, or whether interoperability becomes a neutral standard. Either way, the lesson is the same: the token is table stakes. The business is everything around it.

Thanks for reading!

Found this helpful? Let me know by clicking the like (🤍) icon and share it with someone who might find it helpful too.